6 minute read

The waters off Cape Cod were the source of a major economic industry that contributed to the founding of the United States. Some even say the Revolutionary War was funded by the cod fishery. The trade routes that exchanged goods for revenue quickly doubled as supply routes for the war. The fishing industry was responsible for 35% of the colony’s income, with the next closest sector being livestock at only 25%. Today, the waters off New England are no longer what they used to be.

Warming waters, shifting species

Fishermen who built their livelihoods around cod, haddock, and lobster are now struggling as these species dwindle. The North Atlantic is warming—and fast. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the Gulf of Maine is heating up faster than 99% of the world’s oceans, threatening an ecological upheaval that is already underway. Warm-water species like Atlantic bonito, cobia, and blue crabs are now appearing in Northern waters in record numbers. This transformation is more than a coincidence—it’s yet another consequence of climate change. If these trends continue, New England’s fishing industry, worth billions of dollars, faces an unfamiliar future as traditional cold-water species migrate northward or disappear entirely.

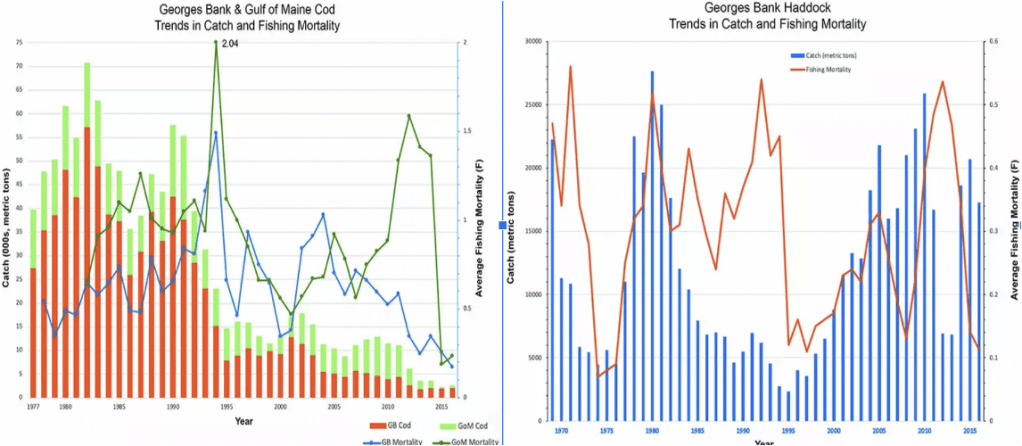

Today, over 400 years after Bartholomew Gosnold gave Cape Cod its American name, NOAA’s stock assessments paint a grim picture for many species off its coasts. While historically removed from early industrial operations, New England’s blue economy faces increasing global pressures. In today’s international seafood market, demand for local species has skyrocketed. Yet, management of the waters and resources has remained quite the same throughout the centuries. After hundreds of years of utilization and exploitation, New England’s waters have indeed paid the price.

The good, bad, and ugly of Management

The first relief came in the 1960s, through The Stratton Act. The first meeting regarding the country’s coastline and waters got the ball rolling, changing some people’s worldviews to include nature and ecosystems, but it had little social meaning. This would lead to the Clean Water Act (CWA), enacted in 1972, ensuring the restoration and maintenance of the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the nation’s waters. What began as people benefiting themselves, the CWA initiated a societal shift; people started caring and advocating for resource management for present and future use. It took something as dramatic as the Cuyahoga River catching fire in 1969 for public outcry.

Another example where public uproar forced management was whaling and its ban under the Marine Mammal Protection Act. Finally, in 1976, the Magnuson-Stevens Act pledged to stop overfishing and rebuild overfished stocks to increase long-term economic and social benefits, ensure a safe and sustainable supply of seafood while protecting habitats and fish needs. This act gave birth to the adaptive management idea two years later. The idea that we don’t know everything finally comes into play, and as data is recorded and released, regulation can change accordingly.

These legislative milestones mark a societal change and the birth of modern marine conservation efforts. Despite decades of policy evolution, the species at the heart of New England’s fisheries have continued to struggle. Gadus morhua, or cod, was once so plentiful that a voyage 18 years preceding the Mayflower named a peninsula and bay after the species. They are one of the core species and a backbone of New England’s pre- and early-industrial fisheries and economy.

Today, cod is a cover name for species like haddock and spiny dogfish. Haddock is comparable to cod, with both having a white flaky texture and flavor. This is due to the species having similar niches and diets, unlike dogfish, which will eat almost anything they can get their mouths around.

A New England Fisheries Management Council study found a steep decline in haddock populations. It doesn’t take a marine biologist to suggest this is due to the same environmental pressures and the attempt to supplement the declining cod fishery.

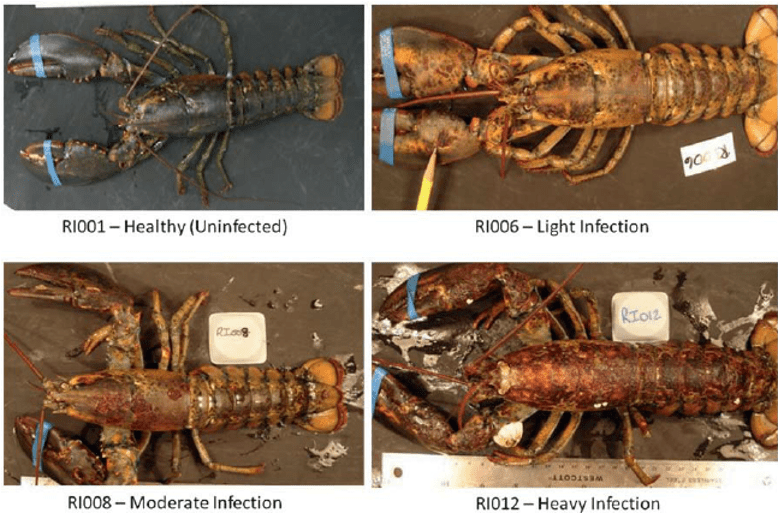

Homarus americanus, American lobsters, an iconic New England symbol, are distancing themselves from the New England coastline. While the Gulf of Maine’s warming waters initially led to a boom in lobster populations, NOAA’s Northeast Fisheries Science Center warns that prolonged exposure to higher water temperatures weakens lobster shells, reduces reproduction, and increases susceptibility to disease. In southern New England, especially Long Island Sound, lobster populations have already collapsed, forcing many lobstermen out of business or northward in search of viable fishing grounds. Like Southern New England’s lobster fishermen, Callinectes sapidus, the Blue Crab, is northbound. They are becoming increasingly frequently encountered over the summer months. They currently struggle to survive northern New England’s harsh winters, but it is possible that continued warming could allow them to establish permanent populations, potentially disrupting native species’ habitats. Proof that this might be becoming the case are states like New York, making management decisions to protect blue crabs.

It is hard to be optimistic about a successful future for the cold water lobster industry in the North East when water warming shows no signs of halting, the species is already moving, a competitor is already filling in the space they left, and lobster fishermen will continue to pull to the North East corner of the United States. The financial burden of New England’s fisheries as a whole, if they continue to struggle, extends beyond the fishermen; it ripples down the chain to seafood processors, distributors, and even restaurants.

Adapting to an Uncertain Future

The clock is ticking, and the hopes for restoring the coastal waters to what they once were are no longer realistic. Adapting to the changing waters is the best course of action for local fishermen. Policymakers must update fishing regulations to reflect the new reality, allowing fishermen to target emerging species with sustainable regulations to prevent repeating past mistakes. Investment in climate-resilient fishing infrastructure, such as diversified gear and flexible permitting systems, could help fishermen navigate the shifting waters.

The livelihood of fishers and the economic health of many coastal communities that rely on fishing are in danger of disappearing. For this reason, an industry worth exploring is large-scale fish farming, particularly in species that can adapt to New England’s warming waters.

New England’s waters are warming, and there’s no turning back. The fish that once defined this region are vanishing, replaced by species that few could have imagined catching here just a decade ago. Whether the industry sinks or swims will depend on how quickly we recognize and respond to these changes. The ocean is speaking—are we listening?

About the Author: Logan Johnson is a fisherman from Cape Cod and a student at the University of Rhode Island. He is passionate about marine ecosystems and the impact of climate change on coastal communities. With firsthand experience on the water and academic research in fish culture and fisheries science, he aims to bridge the gap between science and industry to find sustainable solutions for the future of New England’s fisheries.

This article was written for MAF/APG 471_Sp25, I attest that I am the author of this article and have responsibly referenced my sources throughout the article. I have given professor Lloréns permission to publish it on her website.